The Software Investment Required to Facilitate Energy Efficiency

A more effective grid operating system would dramatically reduce energy costs and create a Jevons Paradox with positive implications across the entire U.S. economy.

The United States is installing clean energy capacity at its fastest pace in history. Yet an expanding share of this potential is going unused. In 2024 alone, California’s grid operator curtailed 3.4 million megawatt-hours of renewable electricity, a 29% increase from the year prior. Texas discarded more than 8 million MWh of wind and solar for the same reason, even as electricity demand reached record highs.

Curtailments across other U.S. markets are accelerating even faster. In the American Southwest, wind curtailments are now six times higher than in 2020. Across the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest, curtailments jumped sixfold in a single year as new renewables came online.

Every megawatt-hour curtailed represents cheap, clean energy that could have displaced fossil generation. Instead, it is wasted, because the grid cannot move, store, or coordinate it in real time. To close this gap, we need smarter, more connected software and systems.

Transmission Congestion is the Biggest Problem at Present

The most visible constraint is transmission congestion. Renewable-rich regions like West Texas and California’s Central Valley routinely generate more power than existing lines can carry to population centers. To preserve system stability, grid operators curtail output.

The economic penalty of this congestion is substantial. In 2023, U.S. grid congestion cost consumers an estimated $11.5 billion in higher power prices. Even after easing in 2024, congestion still imposed nearly $8 billion in annual costs.

Texas illustrates this acutely: wind-rich regions often saturate available transmission, forcing curtailment even as urban demand spikes. In recent years, over 4% of potential wind output in Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) was lost purely due to transmission limits.

The crux of the problem exists at the interconnection queue. As of the end of 2023, roughly 2,600 GW of generation and storage capacity was awaiting grid approval – more than twice the size of the entire U.S. power system today. The queue is now 95% zero-carbon resources, yet historically only ~14% of projects that enter the queue ever reach commercial operation. Twenty years ago, interconnection approvals averaged under two years. Today, they exceed five years. Interconnection timelines exploded because the system was built for a world of slow, centralized power plants, not today’s surge of variable renewables, storage, and speculative projects. Severe underinvestment in transmission, complex cost-allocation rules, staffing bottlenecks, and legacy, manual study processes have turned what used to be a plug-in exercise into a multi-year planning ordeal. At its core, the queue is broken because grid planning software and workflows never scaled to match the pace of the energy transition.

Load Is Exploding, But the Trouble is Figuring Out When and Where

Transmission congestion is the biggest issue today – but as we plan for the future, the biggest issue is energy forecasting uncertainty. Every major planning and dispatch decision in power systems begins with a forecast: how much electricity will be needed, where, and when. When forecasts fail, every downstream investment compounds these errors.

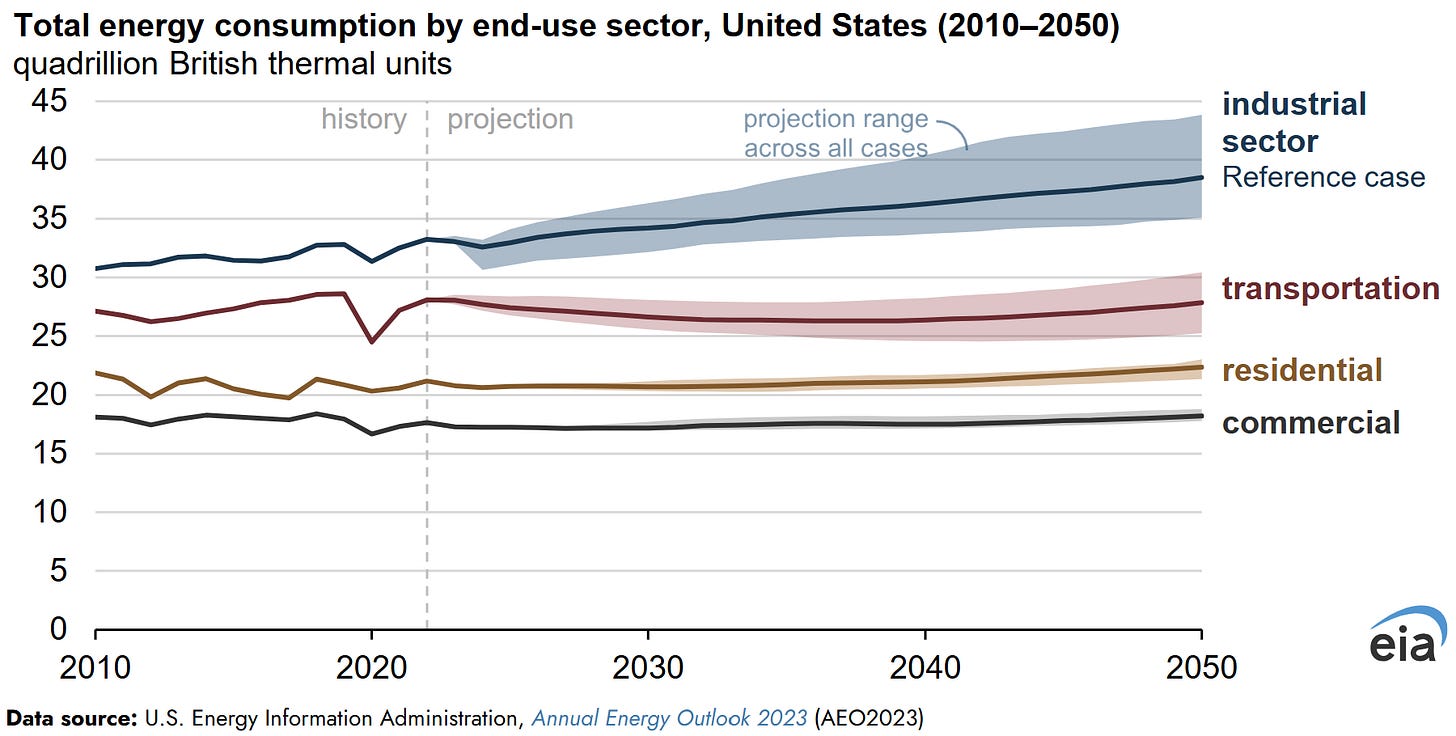

Demand is being reshaped by EV adoption, electrified heating, reshoring of manufacturing, and hyperscale compute. At the same time, supply has become increasingly variable as wind and solar penetration rises.

The Brattle Group now projects U.S. peak load rising 24% by 2030 and 36% by 2035 relative to 2024. But these estimates only materialized over the past year as AI-driven data-center requests surged. Between 2022 and 2024, projections for data-center electricity demand by 2030 varied from near-zero incremental growth to over 1,000 TWh per year. One high-end scenario implied data centers alone could consume one quarter of total U.S. electricity generation by decade’s end. Others detected no measurable national load growth at all.

Utilities are now being asked to invest tens of billions in irreversible infrastructure decisions based on forecasts with five-orders-of-magnitude variance. This is an impossible task – overbuilding and underbuilding have equally costly impacts on energy prices & efficiency. Traditional deterministic forecasting models were not built for this era.

Machine learning, in combination with data from Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), are now reshaping how forecasting works. Utilities are deploying models that ingest weather patterns, demographics, economic data, and device-level smart-meter telemetry.

The World Economic Forum has explicitly called for embedding AI-driven forecasting into energy planning to proactively prevent bottlenecks before they emerge. This is one of the most asymmetric opportunities in the energy system: better predictions upstream save billions in concrete downstream.

The build-utilization gap is also a function of geography and timing. Data centers, semiconductor fabs, and electrified industries are now driving the fastest electricity-demand growth in decades, but often in locations poorly aligned with renewable supply. Northern Virginia, central Ohio, and parts of the Southeast are becoming hubs of compute-driven demand. Meanwhile, the most productive wind and solar resources remain hundreds of miles away.

Reliability Rules Force Clean Power Offline

Even when transmission and demand align, operational rigidity suppresses clean-energy utilization. Grid operators must keep thermal power plants online because of inertia, ramping, and contingency reserves. In California, solar is routinely curtailed at midday not because demand is low, but to preserve headroom for gas plants needed to serve the evening ramp.

We are asking twenty-first-century generation assets to operate within a twentieth-century operating framework. The volatility, granularity, and heterogeneity of resources has changed, but the grid’s coordination architecture has not kept pace.

From Delivery Pipeline to Networked System

Historically, the grid functioned as a one-way delivery pipeline: large generators pushed power through transmission lines to passive consumers. But the modern grid is a dense, bidirectional network of millions of active nodes, including solar rooftops, batteries, EVs, smart appliances, and flexible industrial loads. Each is capable of both consuming and providing power. Distributed networks require a robust operating system to function effectively.

As we project what the future of distributed energy resources may look like, we can draw comparisons from the path that computing took in prior decades. Early computers were isolated. Network protocols like Ethernet and the World Wide Web unified them and unlocked entirely new economic layers: cloud computing, software platforms, digital marketplaces. The grid is now at its pre-protocol moment: highly capable hardware exists without a unified nervous system.

The idea of a “grid operating system” is moving from abstract concept to operational necessity. Earlier this year, Google’s moonshot division, X, launched Project Tapestry, an AI-driven platform intended to unify grid operations across stakeholders. Today, no single entity has a complete real-time picture of the grid. Data remains fragmented across generation companies, Independent System Operators (ISOs), utilities, and consumers. Optimization remains local – Google and their partners are looking to change that.

Batteries Are Scaling Faster Than the Brain to Control Them

More efficient operating systems would also lead to better battery utilization. Battery deployment is growing massively, but coordination has lagged far behind deployment.

Many batteries still operate on rigid heuristics – charging during off-peak hours and discharging during peak windows. Others respond only to localized price signals. There are already documented cases where solar is curtailed while batteries sit idle, simply because no integrated control layer is orchestrating their behavior at the system level.

We are building distributed hardware far faster than distributed intelligence. Without that intelligence, storage underperforms its system-level potential and behaves like a collection of isolated machines rather than a coordinated grid resource.

Software Investment in the Energy Sector Requires Better Economic Incentives

Poor government incentive structures have exacerbated the growing divide between physical and software development. For over a century, utility business models were built around physical capital because of government incentives. The more physical structures that were placed in service, the higher the allowed returns. This produced a persistent capex bias: under cost-of-service regulation, a $100 million substation was a better investment than a $10 million-per-year software solution that achieved the same outcome. The former would go into a utility company’s rate base with a guaranteed return, whereas the latter would be treated as an expense with no markup.

This bias systematically disadvantaged software investment into demand response, efficiency, and DER coordination.

This regulatory dynamic is beginning to shift. New York’s Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management program demonstrated a viable alternative. Instead of building a $1.2 billion substation, Con Edison invested roughly $200 million in distributed resources and demand-side management. Regulators allowed the utility to earn returns on these non-traditional investments and layered in performance incentives.

The results of this 2019 initiative have been quite positive. Con Edison noted 69 MW of peak load reduction, ~$95 million in net customer benefits, and the deferral of massive physical infrastructure spend. This trial clearly demonstrated how software and distributed solutions can compete with concrete if the incentive structure is realigned.

Performance-based regulation is now slowly spreading across leading states, tilting utility economics toward operational performance. Venture capital has noticed. Over the past five years, billions of dollars have flowed into grid software, DER orchestration, forecasting, and energy-market platforms.

Who Controls the Grid’s Digital Backbone?

Today, core grid-control software comes from a small set of industrial vendors and is operated by utilities and ISOs. But as the system evolves toward unified coordination across transmission, distribution, storage, and flexible demand, there exist multiple points of entry for new market participants.

Big Tech has taken notice. Microsoft is deeply embedded in utility cloud and analytics. Amazon provides the infrastructure layer for many energy platforms. Tesla’s AutoBidder now dispatches grid-scale batteries. Consumer technology platforms like Google Nest increasingly touch demand through smart-home ecosystems.

Control of the grid’s digital backbone confers extraordinary leverage. It shapes which assets are dispatched, which services earn revenue, and which market participants gain visibility.

It also raises sovereignty and cybersecurity questions. Electricity is national infrastructure. Regulators will not allow critical grid control to become a black box owned by a single private actor without sovereign safeguards.

The Societal Implications of Better Energy Software

The U.S. needs better grid intelligence to achieve its clean-energy ambitions. As is the case in manufacturing, the physical energy transition is outrunning the digital one.

Better forecasting unlocks better planning. Better orchestration unlocks better utilization. Better market design unlocks better economics.

These are, in large part, software problems with massive economic implications. As energy becomes more readily available, it gets substantially cheaper - cheaper energy would unleash a Jevons Paradox: consumers and businesses alike will use more energy to solve a whole host of problems that push society forward.